Computational Thinking

Frameworks from research and expert practice

Computational Thinking encompasses the practices and knowledge involved in designing computer technologies. It bridges two domains: pedagogy (how we teach programming and computer science) and expert practice (how experienced developers actually design software).

Note: This content was originally written in 2013 as part of my Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches (HDR) memoire. It has been rewritten in 2026 for improved wording and formatting, but the references have not been updated and should be revised to include the substantial body of research on computational thinking from the past 10-15 years. The core synthesis model and framework, however, remain valid and relevant.

Computer Science Education

The concept of “computational thinking” gained prominence when Wing, 2006 proposed it as a framework for rethinking computer science pedagogy. Since then, the field has grappled with defining and teaching the core competencies needed for information technology work.

Computer science curricula are regularly updated to reflect evolving knowledge requirements JTFCC, 2001. The latest revision JTFCC, 2013 shows computational thinking spreading beyond computer science into biology, chemistry, engineering, and economics—driven by the widespread use of data processing and analysis. In parallel, computer science itself is gaining recognition as a core discipline in education Stephenson et al., 2005, with experiments introducing it as early as elementary school Cooper et al., 2010; Barr & Stephenson, 2011; Quinn, 2011.

This context has sparked reflection on three key questions:

What mental patterns does programming induce? Decomposition, abstraction, generalization, pattern recognition, and algorithmic thinking emerge as core cognitive operations Lewandowski et al., 2005; Eckerdal et al., 2005.

How does computational thinking relate to other modes of thought? Researchers explore its connections to logical, mathematical, scientific, analytical, and creative reasoning Papert, 1996; Hu, 2011.

What teaching approaches work best? Effective methods include game design Kurkovsky, 2009, “unplugged” activities that teach concepts without computers Thies & Vahrenhold, 2013, pattern-oriented instruction Muller, 2005, and test-driven development Kollanus & Isomöttönen, 2008.

While this pedagogical research may seem distant from product design practice, it reveals the fundamental cognitive mechanisms at work when designing software systems. The mental operations identified—decomposition, abstraction, pattern recognition, and algorithmic construction—remain largely implicit during requirements gathering and specification work. Making these mechanisms explicit is essential for AI researchers working as computer scientists on domain-specific problems.

Study of Expert Practice in Software Engineering

Before “computational thinking” became popular, researchers were already studying how expert developers actually work. This research took two complementary forms: cognitive psychologists observing and analyzing developer behavior Visser & Hoc, 1990; Detienne, 1995, and expert practitioners reflecting on their own experience to formalize methodologies Parnas, 1972; Dijkstra, 1976.

These studies treat software as a designed artifact Petre, 2009 where problem and solution co-evolve because initial problems are rarely well-defined Dorst & Cross, 2001. Software design requires a general problem-solving strategy that can be characterized along several dimensions Tang & van Vliet, 2012:

Problem-oriented vs. Solution-oriented: Start by exploring and specifying the problem in detail (problem-oriented), or use solution prototyping as a way to understand and define the problem (solution-oriented).

Breadth-first vs. Depth-first: Design the overall system structure before diving into details (breadth-first), or solve one specific part thoroughly before expanding to the whole (depth-first).

These high-level strategies combine with software-specific tactics:

Procedural vs. Declarative Detienne, 1995: Build from actions and execution flows toward data structures (procedural), or start with data objects and add behaviors (declarative).

Prospective vs. Retrospective Visser & Hoc, 1990: Work forward from inputs to desired outputs (prospective), or work backward from the goal state (retrospective).

Developers also employ cognitive mechanisms to manage complexity that would otherwise be “too big for the head” Petre, 2009. These include simplification, transformation into more tractable representations, decomposition, constraint relaxation, reasoning by analogy, and abstraction to more general problems. Because problems and solutions co-evolve, developers must master provisionality Petre, 2009—the ability to focus on one aspect while temporarily setting others aside, and to defer decisions when needed.

Focusing requires separation of concerns Dijkstra, 1982: identifying which aspects (behaviors, functionalities) span multiple modules and which cluster within single components Ali et al., 2010. This dual separation—into components and into concerns—helps optimize system architecture.

Throughout this work, developers build and maintain a structural schema of both problem and solution Corritore & Wiedenbeck, 1999. This mental model guides progress, supports backtracking, and enables resumption after interruptions Parnin & Rugaber, 2012. Developers externalize these schemas through visual representations—diagrams and sketches—to support reflection, overview, and communication Jackson, 2010; Ikeya et al., 2012.

The architecture schema plays a central role Taylor & van der Hoek, 2007 because it sits at the problem-solution interface. It captures the initial decomposition decisions, allows validation of the module structure Parnas, 1972, provides an overview of the solution space, and tracks implementation progress.

In the solution space, code writing is central but not the only activity. Early in design, developers often latch onto a “pet concept” Baker & van der Hoek, 2010—an identifiable, plausible (or simply interesting) solution idea that helps focus exploration. This pet concept becomes a vehicle for testing assumptions, questioning requirements, and building initial prototypes. Developers then simulate their emerging solutions, either mentally or through executable code Visser & Hoc, 1990, to validate ideas and guide next steps.

Throughout this process, the designer’s judgment is constantly at work Wing, 2008; Hu, 2011, evaluating system complexity, the fit between functions and architecture, the coherence of decomposition decisions, and the relevance of the solution for actual user needs.

Synthesis: A Model of Computational Thinking

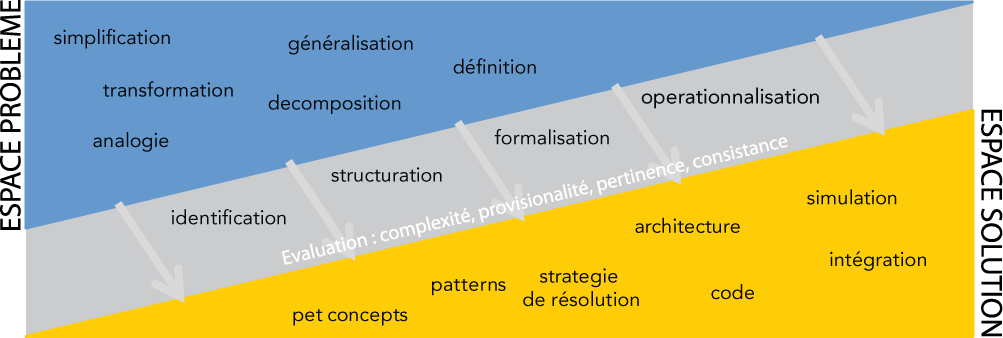

The figure below maps the operations and objects identified in the computational thinking literature onto a temporal model of software design. It builds on the classical design thinking framework Cross, 2011, following Petre, 2009’s insight that software is a designed artifact like any other.

Figure: Model of computational thinking operations and objects in the general software design process

The diagram shows how computational thinking unfolds across time (left to right) through distinct but interconnected zones:

Problem Space (blue, top left): Early in the design process, developers work directly with the problem through cognitive operations: simplification, transformation, analogy, decomposition, generalization, and definition. These operations build understanding of what needs to be solved and why, without yet committing to implementation forms.

Bridging Operations (gray, top middle): As problem understanding matures, four critical operations transform this understanding into structured representations that can guide implementation: identification (recognizing key elements), structuration (organizing relationships), formalization (creating precise specifications), and operationalization (defining how concepts will function). These operations are the pivot point where abstract problem work becomes actionable design.

Intermediate Artifacts (gray, middle): The bridging operations produce intermediate design objects—patterns (recognizable solution templates), pet concepts (initial solution ideas), and resolution strategies (planned approaches). These artifacts capture design decisions in forms that can be communicated, evaluated, and refined.

Continuous Evaluation (diagonal line): Throughout this progression, judgment operates continuously, assessing complexity (is this manageable?), provisionality (what can be deferred?), pertinence (does this address real needs?), and consistency (do the parts cohere?). Evaluation is not a gate but an ongoing thread connecting all stages.

Solution Space (yellow, bottom right): Later in the process, work becomes concrete: architecture design establishes system structure, code writing implements functionality, simulation validates behavior, and integration assembles components. These artifacts embody upstream decisions and can be tested and deployed.

This model serves three purposes:

Synthesis: It captures the core concepts of application design in a unified framework. Intelligent systems design is a special case within this broader structure.

Bridging clarity: It makes explicit how bridging operations (identification, structuration, formalization, operationalization) transform problem understanding into solution guidance through intermediate artifacts.

Methodology: It provides a foundation for understanding and improving design methods by surfacing the cognitive processes that usually remain implicit and showing their temporal relationships.

References

Ali, M.S. et al. (2010). A systematic review of comparative evidence of aspect-oriented programming. Information and Software Technology, 52(9), pp.871–887.

Baker, A. & van der Hoek, A. (2010). Ideas, subjects, and cycles as lenses for understanding the software design process. Design Studies, 31(6), pp.590–613.

Barr, V. & Stephenson, C. (2011). Bringing computational thinking to K-12: what is Involved and what is the role of the computer science education community? ACM Inroads, 2(1), pp.48–54.

Cooper, S., Pérez, L.C. & Rainey, D. (2010). K–12 computational learning. Communications of the ACM, 53(11), pp.27–29.

Corritore, C.L. & Wiedenbeck, S. (1999). Mental representations of expert procedural and object-oriented programmers in a software maintenance task. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 50(1), pp.61–83.

Cross, N. (2011). Design thinking: understanding how designers think and work. Oxford, UK: Berg Publishers.

Detienne, F. (1995). Design Strategies and Knowledge in Object-Oriented Programming: Effects of Experience. Human-Computer Interaction, 10(2), pp.129–170.

Dijkstra, E.W. (1976). A Discipline of Programming. Prentice Hall PTR.

Dijkstra, E.W. (1982). On the role of scientific thought. In Selected writings on computing: a personal perspective. Springer-Verlag, pp. 60–66.

Dorst, K. & Cross, N. (2001). Creativity in the design process: co-evolution of problem–solution. Design Studies, 22(5), pp.425–437.

Eckerdal, A., Thuné, M. & Berglund, A. (2005). What does it take to learn “programming thinking”? In Proceedings of the 2005 international workshop on Computing education research - ICER ‘05. ACM Press, pp. 135–142.

Hu, C. (2011). Computational thinking - What It Might Mean and What We Might Do About It. In Proceedings of the 16th annual joint conference on Innovation and technology in computer science education - ITiCSE ‘11. ACM Press, pp. 223–227.

Ikeya, N., Luck, R. & Randall, D. (2012). Recovering the emergent logic in a software design exercise. Design Studies, 33(6), pp.611–629.

Jackson, M. (2010). Representing structure in a software system design. Design Studies, 31(6), pp.545–566.

JTFCC (2001). Computing Curricula 2001 Computer Science. ACM / IEEE.

JTFCC (2013). Computer Science Curricula 2013: The Joint Task Force on Computing Curricula. ACM / IEEE. Available at: http://ai.stanford.edu/users/sahami/CS2013/.

Kollanus, S. & Isomöttönen, V. (2008). Test-driven development in education: experiences with critical viewpoints. In Proceedings of the 13th annual conference on Innovation and technology in computer science education. ACM, pp. 124–127.

Kurkovsky, S. (2009). Engaging students through mobile game development. Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, 41(1), pp.44–48.

Lewandowski, G. et al. (2005). What novice programmers don’t know. In Proceedings of the 2005 international workshop on Computing education research - ICER ‘05. ACM Press, pp. 1–12.

Muller, O. (2005). Pattern oriented instruction and the enhancement of analogical reasoning. In Proceedings of the 2005 international workshop on Computing education research - ICER ‘05. ACM Press, pp. 57–67.

Papert, S. (1996). An exploration in the space of mathematics educations. International Journal of Computers for Mathematical Learning, 1(1), pp.95–123.

Parnin, C. & Rugaber, S. (2012). Programmer information needs after memory failure. In 20th IEEE International Conference on Program Comprehension (ICPC). IEEE, pp. 123–132.

Parnas, D. (1972). On the criteria to be used in decomposing systems into modules. Communications of the ACM, 15(12), pp.1053–1058.

Petre, M. (2009). Insights from expert software design practice. In Proceedings of the 7th joint meeting of the European software engineering conference and the ACM SIGSOFT symposium on The foundations of software engineering - ESEC/FSE’09. ACM Press, pp. 233–242.

Quinn, H. (Committee on C.F. for the N.K.-12 S.E.S.) (2011). A Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas. National Academy of Sciences. Available at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13165.

Stephenson, C. et al. (2005). The new educational imperative: Improving high school computer science education. Computer Science Teachers Associations: 07_06.

Tang, A. & van Vliet, H. (2012). Design Strategy and Software Design Effectiveness. IEEE Software, 29(1), pp.51–55.

Taylor, R.N. & van der Hoek, A. (2007). Software Design and Architecture: The once and future focus of software engineering. In Future of Software Engineering (FOSE ‘07). IEEE, pp. 226–243.

Thies, R. & Vahrenhold, J. (2013). On plugging “unplugged” into CS classes. In Proceeding of the 44th ACM technical symposium on Computer science education - SIGCSE ‘13. ACM Press, pp. 365–370.

Visser, W. & Hoc, J.-M. (1990). Expert Software Design Strategies. In Psychology of Programming. pp. 239–274.

Wing, J.M. (2006). Computational thinking. Communications of the ACM, 49(3), pp.33–34.

Wing, J.M. (2008). Computational thinking and thinking about computing. Philosophical transactions. Series A, Mathematical, physical, and engineering sciences, 366(1881), pp.3717–25.